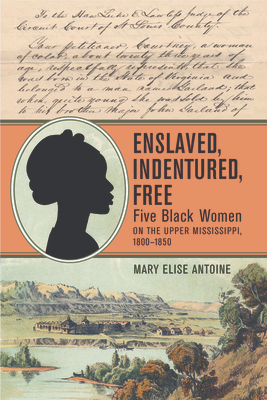

Enslaved,

Indentured, Free: Five Black Women on the Upper Mississippi, 1800-1850

Mary Elise Antoine

US History

Wisconsin Historical

Society Press

October 5, 2022, 240 pp,

Ebook $11.99; paper $24.95

Buy on Wisconsin Historical Society

About the Book

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 made slavery

illegal in the territory that would later become Illinois, Indiana, Michigan,

Ohio, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota. However, many Black individuals’ rights

were denied by white enslavers who continued to hold them captive in the

territory well into the nineteenth century. Enslaved, Indentured, Free shines a

light on five extraordinary Black women—Marianne, Mariah, Patsey, Rachel, and

Courtney—whose lives intersected in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, during these

seminal years.

Focusing on these five women, Mary Elise Antoine explores the history of slavery in the Upper Mississippi River Valley, relying on legal documents, military records, court transcripts, and personal correspondence. Whether through perseverance, self-purchase, or freedom suits—including one suit that was used as precedent in Dred and Harriet Scott’s freedom suits years later—each of these women ultimately secured her freedom, thanks in part to the bonds they forged with one another.

My Review

Using public

records available, Mary Elise Antoine weaves together a story of early settlement

on the upper Mississippi, focused on Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Beginning

with Marianne, a freeborn black woman who remained free, the author researched

and shares about the lives of four other women whose lives touched.

Marianne was born

in the country along the southern Mississippi in the mid eighteenth century,

and married three times to French traders. Her second husband relocated to

Prairie du Chien. She was a unique figure who owned land, farmed, bore thirteen

children and practiced healing ways. The author notes that Prairie du Chien was

already diverse with mixed cultures. “In the early nineteenth century, race did

not automatically exclude people of color from various institutions on the prairie.

However, when white American men brought people of African heritage with them to

the prairie, they also brought racial inequality,” she writes.

The second subject,

Mariah, was brought to Prairie du Chien in 1816, one of 200 enslaved,

indentured, or hired working people brought to the area between 1816 and 1845,

almost all by members of the US Army. Because slavery was illegal in Illinois

Territory, Mariah’s owner changed the sixteen-year-old’s legal status to

indentured. Mariah later married a young soldier, though was “rented” by her

owner to others. When her owner left the area before her servitude was

concluded, he forced her to pay the rest of her contract in order to claim her

freedom. She and her husband divorced in 1839; she subsequently remarried and

moved to a home on land owned by Marianne.

A third woman,

Patsey, was brought to the area by the Indian agent in 1829. Again, the agent

forced Patsey into indentured servitude to get around the law; the indentured

work-around was apparently a common ruse, legally recorded wherever the family

moved, as well as moving their slaves in an out of territory where slavery was

illegal, or calling them variably servant or slave. Patsey had children who

were also indentured.

Courtney was

brought to Prairie du Chien as a servant for an army captain who was allowed to

claim her as an expense to his account, asking a few dollars a month

compensation, her clothing and one ration of food per day. He also provided a

description: five foot-four, black skin, eyes and hair. This girl was eventually

sold several times and moved to different locations in the area, even leaving

her son in slavery to one family. She finally was moved to St. Louis.

Rachel had been

purchased in St. Louis for a soldier with a young family stationed in Prairie

du Chien. When no longer needed, she was returned to St. Louis and sold again,

but this time Rachel took advantage of a Missouri law that allowed enslaved

persons to sue for their freedom based on prior residence in a free territory. she

filed suit in 1834 which was rejected for a word choice, being called a servant

by the soldier. With the help of her attorney, she appealed. During the time,

the attorney also filed a petition for Courtney, both of which were successful

in 1836. Courtney and her son returned to Prairie du Chien where she married

and went to live on land owned by Marianne.

The

text is somewhat dry and filled with much speculation as well as factual information

derived from public records as there are little or no personal records from

these women. The diligent research was excellent. Events of the time were

overlaid to provide some color. Laid out in seven chapters, five for the women

portrayed and two others describing circumstances and life at the time, the

book is a lively portrayal of life on the new frontier. Images of noted

individuals, places, and records and notes accompanying the text provide a nice

variation.

About the Author

Mary Elise Antoine is president of the Prairie

du Chien Historical Society and former curator at Villa Louis. She is the

author of the War of 1812 in Wisconsin and coeditor, with Lucy

Eldersveld Murphy, of Frenchtown Chronicles of Prairie du Chien.

No comments:

Post a Comment